Introduction to Regular Expressions

A couple of years after the Death Star exploded, a hot-shot reporter at the Daily Planet heard that children in the Shire were starting to act strangely. Our supervisor sent some grad students off to find out what was going on. Every student's notebook containing measurements of background evil levels (in milliVaders) at various locations in the Shire was later transcribed and stored as a data file.

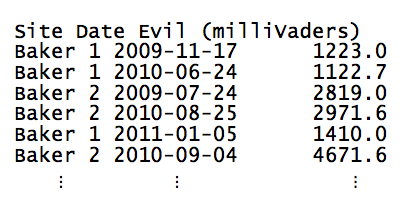

Our job is to read 20 or 30 of these data files, each of which contains several hundred measurements of background evil levels, and convert them into a uniform format for further processing. Each of the readings has the name of the site where the reading was taken, the date the reading was taken on, and of course the background evil level in milliVaders. The problem is, these files are formatted in different ways. Here is the first one:

A single tab character divides the fields in each row into columns. The site names contain spaces, and the dates are in international standard format: four digits for the year, two for the month, and two for the day.

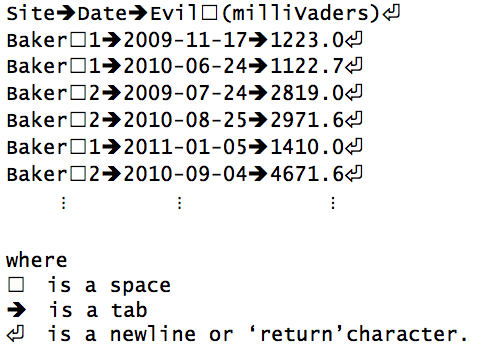

Here is that same table with those characters visualised. Note how we have a not-too-helpful mix of tabs and spaces in the different lines of the file.

Tabs vs. Spaces

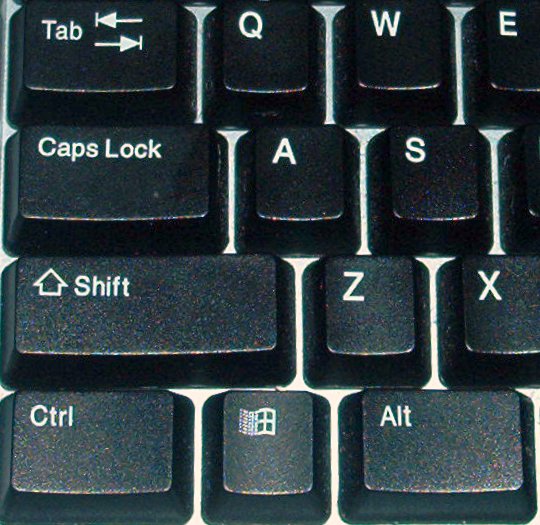

Remember typewriters? Heavy mechanical devices that used physical force to ram a piece of type on the end of a stick at a page, squashing down an inky ribbon to leave a stamped image of a letter or number. Laying out tables on these machines was a time consuming task that required a lot of patient and accurate use of the space and backspace keys. Pretty soon, typewriter manufacturers invented the tabulate or tab key, a single button that moved the current printing position a specified distance and really reduced the work that was done to layout a rudimentary table. The tab lives on in modern computer keyboards and has pretty much the same function: it represents a gap between columns in a table and (usually) moves the cursor a much greater number of pixels than the space bar does. The tab key usually lives in the upper left of the keyboard.

(source: Wikipedia)

Since tab and space are two different keys on the keyboard, the coded message the keyboard sends through to the computer when each key is pressed is completely different, the code for the tab key is represented \t while the code for the space character is usually represented \s (the slashes differentiate them from the usual t and s characters). This means that in strings tabs and spaces are different things to the computer.

A fly in this ointment is that the program that is showing the text strings through the screen is able to render the \t and \s however it likes. Sometimes the program will show the \t as say, 40 empty pixels and the \s as 10 pixels but could display them both as 10. It could even choose to show them as completely different characters, a common thing is to show \t as arrows. So we can't trust what we see on screen, until we really know the program we are using to edit text. When we need to process the programatically we need to be very aware of the encoding differences between tab - \t and space - \s to express clearly what we want of the computer program.

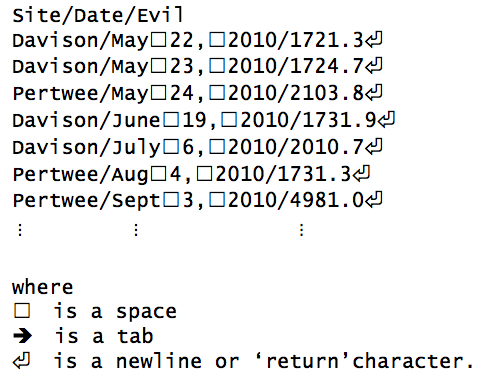

Let's have a look at the second notebook:

Clearly this is very different to the first. It uses slashes as separators. There don't appear to be spaces in the site names, but the month names and day numbers vary in length. What's worse, the months are text, and the order is month-day-year rather than year-month-day.

We could parse these files using basic string operations, but it would

be difficult. A better approach is to use regular

expressions. A regular expression is

just a pattern that can match a string. They are actually very common:

when we say *.txt to a computer, we mean, "Match all of the filenames

that end in .txt." The * is a regular expression: it matches any

number of characters.

The rest of this chapter will look at what regular expressions can do, and how we can use them to handle our data. A warning before we go any further, though: the notation for regular expressions is ugly, even by the standards of programming. Se're writing patterns to match strings, but we're writing those patterns as strings using only the symbols that are on the keyboard, instead of inventing new symbols the way mathematicians do. The good news is that regular expressions work more or less the same way in almost every programming language. We will present examples in Python, but the ideas and notation transfer directly to Perl, Java, MATLAB, C#, and Fortran.